|

Figure 24-1: Atlanto-occipital joint architecture. (From White A, Panjabi M. Clinical Biomechanics of the Spine. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1990.)

Open as PDF Open as JPEG |

|

Figure 24-2: Atlanto-occipital joint movement. (A) Flexion. (B) Extension. (C) Left side flexion. (D) Conjunct right rotation.

Open as PDF Open as JPEG |

|

Figure 24-3: Atlantoaxial joint architecture. (A) Left lateral joint. (B) Median joint complex.

Open as PDF Open as JPEG |

|

Figure 24-4: Atlantoaxial joint movement. (A) Flexion. (B) Extension. (C) Left rotation (x marks the axis of rotation). (D) Right side flexion.

Open as PDF Open as JPEG |

|

Figure 24-5: Craniovertebral ligamentous system, coronal view.]

Open as PDF Open as JPEG |

|

Figure 24-6: (A) Uncovertebral joint. (B) Transverse clefting of the interbody joint (disk).

Open as PDF Open as JPEG |

|

Figure 24-7: (A) Midcervical flexion. (B) Midcervical extension. (C) Midcervical rotation left and side flexion.

Open as PDF Open as JPEG |

|

Figure 24-8: Neutral zone. (A) Normal. (B) Hypermobile. EZ, elastic zone; NZ, neutral zone; ROM, range of motion.

Open as PDF Open as JPEG |

|

Figure 24-9: Craniovertebral muscles. (A) Posterial suboccipitals muscles. (B) Short upper cervical flexor muscles.

Open as PDF Open as JPEG |

|

Figure 24-10: Scalene muscles.

Open as PDF Open as JPEG |

|

Figure 24-11: Wall slide deep neck flexor muscle recruitment, palpating for unwanted superficial muscle activity.

Open as PDF Open as JPEG |

|

Figure 24-12: Short flexor muscle strengthening over a towel roll with slight head lift-off. The patient no longer palpates, because the superficial muscles must now be active to lift the weight of the head against gravity. The neck should not lose contact with the towel, or the chin poke forward, because this is a sign of excessive anterior translation caused by relative dominance of sternocleidomastoid and scalenes substituting for the weaker deep neck flexors.

Open as PDF Open as JPEG |

|

Figure 24-13: A nod lift-off motion can also be performed supported on a high incline. The patient is instructed to nod to the point of cervical spine neutral, and then just lift the head off the supporting surface to take the weight of the head as resistance. The neutral posture of the neck must be maintained, not allowing dominant superficial muscles to cause a chin poke of anterior translation.

Open as PDF Open as JPEG |

|

Figure 24-14: Return to neutral in sitting to recruit the segmental extensors. (A) Start in the forward flexed position. (B) Initiate segmental extension starting at the upper thoracic spine. (C) Continue the extension up the cervical spine to the neutral position.

Open as PDF Open as JPEG |

|

Figure 24-15: Retraining a weak right superior oblique muscle by applying autoresistance to atlanto-occipital joint side flexion into extension on the same side.

Open as PDF Open as JPEG |

|

Figure 24-16: Concentric muscle contraction into the right extension quadrant over a foam roll or rolled towel. Palpation will encourage more local recruitment.

Open as PDF Open as JPEG |

|

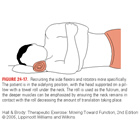

Figure 24-17: Recruiting the side flexors and rotators more specifically. The patient is in the sidelying position, with the head supported on a pillow with a towel roll under the neck. The roll is used as the fulcrum, and the deeper muscles can be emphasized by ensuring the neck remains in contact with the roll decreasing the amount of translation taking place.

Open as PDF Open as JPEG |

|

Figure 24-18: Strengthening in functional movement patterns. With the patient sitting, the therapist palpates at the affected level as the patient performs the motion against the resistance of the therapist.

Open as PDF Open as JPEG |

|

Figure 24-19: Strengthening in functional movement patterns using autoresistance. (A) Concentric contractions into the left flexion quadrant. (B) Eccentric contractions back into the right extension quadrant early in range).

Open as PDF Open as JPEG |

|

Figure 24-20: Range of motion exercises on a foam wedge. Allows non-weight-bearing motion, combining rotation and side flexion with flexion- extension.

Open as PDF Open as JPEG |

|

Figure 24-21: Stretching the posterior suboccipital muscles using the craniovertebral flexion head-nod exercise.

Open as PDF Open as JPEG |

|

Figure 24-22: Stretching into the middle to low cervical erector spinae at the wall.

Open as PDF Open as JPEG |

|

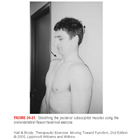

Figure 24-23: Stretching the scalene muscles-first rib fixed, side flexion away, and slight rotation toward the affected side at the wall.

Open as PDF Open as JPEG |

|

Figure 24-24: Sternocleidomastoid stretch-extension, side flexion away from and rotation toward the side being treated.

Open as PDF Open as JPEG |

|

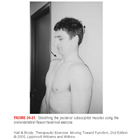

Figure 24-25: Stretching the levator scapula-arm overhead (scapular upward rotation), scapular depression, side flexion away, rotation away from affected side, and flexion.

Open as PDF Open as JPEG |

|

Figure 24-26: Stretching the upper fibers of the trapezius-scapular depression, neck flexion, side flexion away, and rotation toward the affected side.

Open as PDF Open as JPEG |

|

Figure 24-27: Alternative wall slide exercise. (A) Contralateral rotation lengthens the right levator scapula muscle. (B) Ipsilateral rotation lengthens the upper fibers of the right trapezius muscle.

Open as PDF Open as JPEG |

|

Figure 24-28: Dural stretch with manual stabilization and fixation of lateral shear.

Open as PDF Open as JPEG |

|

Figure 24-29: Dural stretch in supine lying with a belt wrapped over the shoulder and around the knee to maintain scapular depression. (A) For median nerve bias, the arm, flexed at the elbow, is abducted to the tension point and externally rotated, with the forearm supinated and the wrist and fingers extended. The elbow is then slowly extended to produce the stretch. (B) For radial nerve bias, the arm, flexed at the elbow, is abducted and internally rotated, the forearm is pronated, with the wrist flexed. The stretch is produced by slowly extending the elbow. (C) For ulnar nerve bias, the arm, flexed to a right angle at the elbow, is abducted and externally rotated, the forearm is pronated, with the wrist extended. The stretch is produced through further flexion of the elbow.

Open as PDF Open as JPEG |

|

Figure 24-30: To determine the stability of the cervical spine during dynamic upper extremity movements, the neck can be observed or palpated during bilateral or unilateral arm elevation in the relaxed upright posture, and then repeated with the cervical spine under the dynamic control of a preset nod. If recruitment of the deep segmental stabilizers decreases the amount of translation, there is a degree of dynamic stability present.

Open as PDF Open as JPEG |

|

Figure 24-31: Levator scapula stretch: fixing C4 to prevent right lateral translation.

Open as PDF Open as JPEG |

|

Figure 24-37: (A) Axial extension. (B) Forward head position: minimal midcervical lordosis. (C) Forward head position: excessive midcervical lordosis.

Open as PDF Open as JPEG |

|

Figure 24-38: Lying on an Epifoam roll.

Open as PDF Open as JPEG |